Could the developments of the education system in Vietnam show one pathway to establishing – and then transforming – conventional schooling? Drawing on a series of interviews as well as a trip to Vietnam, the first post in this 4-part series from Thomas Hatch discusses how Vietnam has achieved near universal education at a relatively high level of quality. Subsequent posts will examine the efforts to shift the Vietnamese educational system to a focus on competencies and some of the critical issues that have to be addressed in the process. For other posts related to Vietnam, see Achieving Education for All for 100 Million People: A Conversation about the Evolution of the Vietnamese School System with Phương Minh Lương and Lân Đỗ Đức (Part 1); Looking toward the future and the implementation of a new competency-based curriculum in Vietnam: A Conversation about the Evolution of the Vietnamese School System with Phương Lương Minh and Lân Đỗ Đức (Part 2); Then Evolution of an Alternative Educational Approach in Vietnam: The Olympia School Story Part 1 and Part 2; and Engagement, Wellbeing, and Innovation in the Wake of the School Closures in Vietnam: A Conversation with Chi Hieu Nguyen (Part 1 and Part 2).

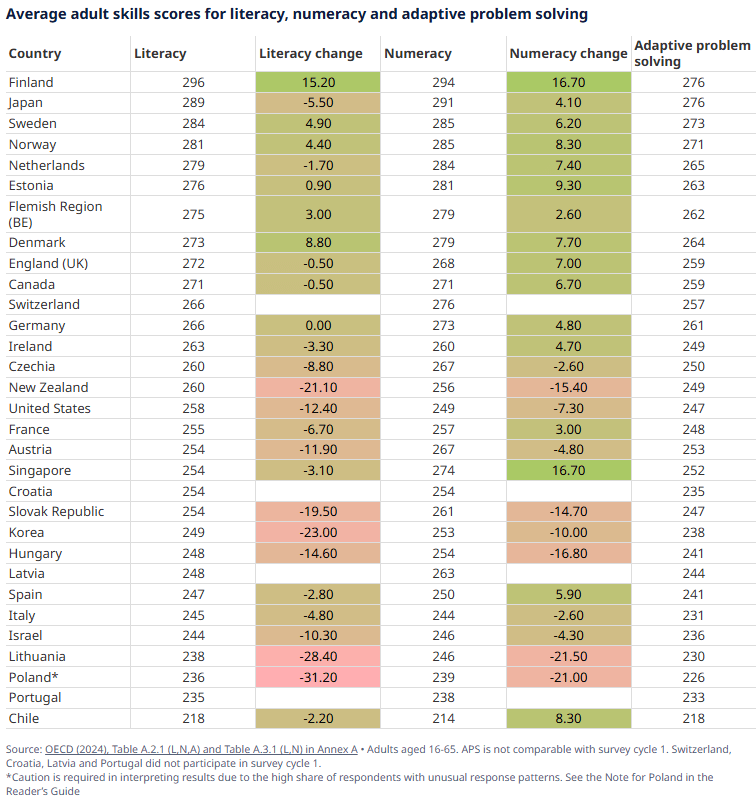

What’s surprising about Vietnam’s educational system? For many, it’s Vietnam’s high performance on the PISA tests often used to gauge educational quality. Since 2012, Vietnam’s 15-year-olds have had some of the highest average PISA scores in reading, math, and science in comparison to other developing economies. Average math scores, in particular, are comparable to or better than the average scores of some of the richest economies in the world, including the United States. In addition, according to the OECD, 34% of Vietnamese students were “among the most disadvantaged students who took the PISA test in 2022,” yet their average score in mathematics was one of the highest for students of similar socio-economic backgrounds, and the gap between the students in the highest and lowest socio-economic categories was smaller than the OECD average.

As surprising as those results might be, as someone who has been studying “higher“ and “lower“ performing education systems such as Finland and Singapore, several other aspects of Vietnam’s educational system stand out as well:

- Vietnam has achieved near universal education at a relatively high level of quality in a country with almost 100 million people – roughly 10 times the populations of Finland and Singapore combined.

- Despite these differences, some, though not all, of the key factors that support high system performance in Finland and Singapore seem to apply in Vietnam.

- Vietnam has already launched major initiatives to shift the entire education system to focus on competency-based goals and more student-centered instruction, a move that “high performing” systems like Finland and Singapore are still trying to figure out how to make.

All of this has been achieved in a country with 54 different ethnic groups, where the city of Hanoi, on its own, has a larger population than all of Singapore and where the budget is about 22 Billion USD, compared to about 95 Billion USD in Finland.

In another 20 years, will Vietnam be leading the way in transforming the conventional model of schooling that has dominated education for more than 100 years? To explore this question, in the first part of this series of posts, I share some of my observations about the key developments in the Vietnamese education system over the past thirty years.

“Will Vietnam be leading the way in transforming the conventional model of schooling that has dominated education for more than 100 years?“

Improvements in enrollment and access to schooling for all students

As many countries with developing education systems continue to try to provide access to education for all students, Vietnam has achieved school enrollment rates near 100% in kindergarten, primary, and lower secondary schools. A significant amount of that growth took place in less than 20 years, between 1990 and 2012. Enrollment in secondary schools in particular tripled in only 14 years, rising from about 23% in 1992 to almost 75% by 2006. Although secondary school enrollment remains a concern, as there has been only a slight increase since then, the mean years of schooling for adults in Vietnam is still higher than expected, given its per capita income.

Evidence of Educational Quality & Equity: PISA and beyond

Although many countries are working to expand access to schooling, educational quality remains a critical concern around the world. But the results of the 2012 PISA tests suggests that Vietnam has been able to increase both access and quality significantly. Those results showed that by 2014, Vietnam’s 15-year-olds were 17th in math and 19th in reading out of 65 countries. More astoundingly, that performance made Vietnam an outlier – performing significantly higher in both reading and math than other education systems with a comparable GDP.

These striking outcomes garnered considerable attention and generated a number of critiques that have raised legitimate concerns about the accuracy of the results. Notably, students who drop out of school in Vietnam after 9th grade are not included in the sample taking the PISA test, inflating the average PISA scores. In addition, one report suggests that some Vietnamese students participating in the PISA tests have been encouraged to do their best to “bring Vietnam honor,” and in one case, students received t-shirts identifying them as PISA participants. At the same time, this report concludes that, although these problems could have had some effect on Vietnam’s scores, statistical adjustments for those issues “do not change the overall finding that Vietnam’s PISA performance was exceptional” and that it substantially outperformed other countries of similar income levels.

Several other sources of data confirm the significant growth in Vietnamese students’ educational performance. First of all, by 2019, 96% of the population over 15 could read and write. Vietnam’s own tests of mathematics and language in 2001 and 2007 also show what analysts describe as “very large increases over six years.” Comparisons with other developing education systems in India, Peru, and Ethiopia carried out by the Young Lives project show that the scores of the Vietnamese students continue to grow significantly over time, leading to the conclusion that a year of primary school in Vietnam is “considerably more productive in terms of quantitative skill acquisition” than a year of schooling in the other countries. As a consequence, in Vietnam, almost 19 out of every 20 10-year-olds can add four-digit numbers, and 85% can subtract fractions – proportions of correct answers similar to many OECD countries and substantially higher than those in other countries with similar GDP.

Although there are still some differences in the enrollments and performance of students from different ethnic minority groups, particularly at the upper secondary level, Vietnamese education policy and funding explicitly recognize the rights of all students to learn their own language and preserve their cultures. Article 11 of the Vietnamese Constitution states: “Every ethnic group has the right to use its own language and system of writing, to preserve its national identity, to promote its fine customs, habits, traditions and culture.” In addition, Phuong Luong, a researcher from Vietnam National University and the Vietnam National Institute of Educational Sciences estimates that the Vietnamese government has over 130 different policies to support ethnic minorities, including 10 key policies on introduction of ethnic minority languages and cultures into curriculum; more than 20 policies for financial support/scholarships, exemption or reduction of tuition fees, housing and accommodations for ethnic minority students; and five different policies for recruiting ethnic minority teachers. Most recently, the Vietnamese government has implemented regulations abolishing school fees for public education from preschool to high school. Previously, even public schools charged families fees for things like uniforms, textbooks, and other purposes. Although estimated to cost the government about 1.3 billion USD, these new regulations, along with new limits on costly supplementary tutoring sessions, are designed to ease the financial burdens of education for all students, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Next week: Building the capacity for high quality education at scale: Can Vietnam transform the conventional model of schooling (Part 2)