What does it take to support young children’s development in rural China? In this post, Thomas Hatch shares what he learned in a conversation this past May with Guangmin Li, Secretary General of the Beijing Western Sunshine Rural Development Foundation, and her colleagues. Established in 2006, the Foundation is dedicated to meeting needs of children in some of the most remote areas of China, many of whom have been left behind to live with grandparents or to attend boarding schools as their parents have moved to get jobs in larger cities. This post is the third in a series on early childhood education that includes articles from Norway and India.

What does life look like for children in rural China? Even many people living in China’s rapidly expanding urban centers at the turn of the 21st Century had relatively little direct knowledge of the daily living experiences throughout China’s rural provinces; but that began to change when a young college student, Shang Lifu, crisscrossed rural China from 1998 – 2002, biking and walking more than 90,000 miles. He took almost 10,000 photos and wrote a report that helped people in urban areas get to know parts of China that many had never seen. Lifu’s reporting inspired many initiatives to support life and education in rural China, including the establishment of the Western Sunshine Foundation. Since 2006, the Western Sunshine Foundation has been dedicated to the revitalization and development of remote areas in China with a special focus on providing teachers, students and children with opportunities for self-improvement. The foundation has pursued that mission by addressing three problems affecting youth development and education in some of the most remote areas of China:

- A lack of educational facilities and materials for children and adolescents aged 3 – 16

- Little or no support for the personal, social, and emotional development of children in boarding schools

- Limited opportunities for the training and development of teachers.

County, Gansu Province, China leaving the cave where they had school

Supporting the “Last mile” for early childhood education in rural China

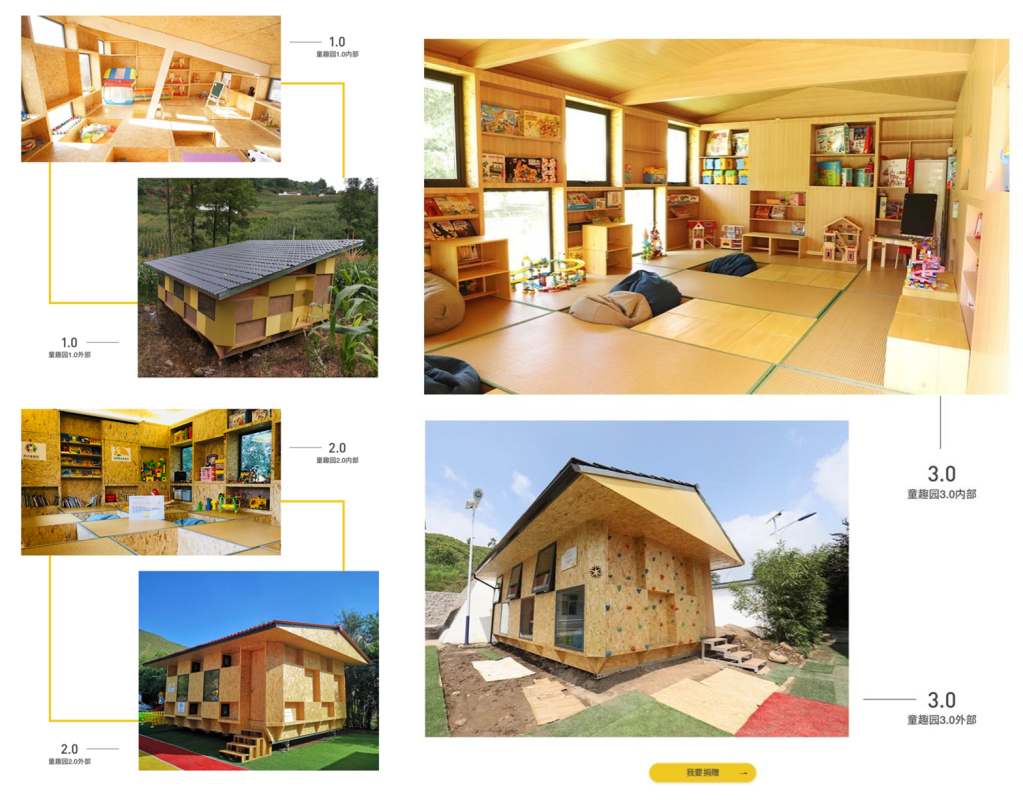

In 2006, China was still in the relatively early stages of an ongoing effort to enroll children across the country in early childhood education. In one of its first initiatives, the Western Sunshine Foundation focused on the “last mile” of this enrollment effort by trying to develop a replicable, sustainable model for early childhood education that could work in areas where there were fewif any places to gather for school and few materials other than the natural resources these environments. A key part of that approach was the design for small, “micro-kindergartens” (referred to as “Sunshine Kindergartens”) that could serve children from 3- 6 years old and that could be constructed relatively easily even in the harshest conditions. The design of the Sunshine Kindergartens feature lightweight, prefabricated materials that can be assembled quickly by local volunteers. That design evolved through three iterations, and as of December 2023, the project had built 192 Sunshine Children’s Parks in more than 25counties in 14 provinces across China, serving over 30,000 children. In addition to building the facilities, the Foundation sought to make the kindergartens sustainable by also providing training and support for teachers and offering guidance to help local governments manage these small, decentralized education centers.

Filling a caretaker role for “left behind” children

Since those early days of the Foundation, the declining births in China and the migration to urban centers have contributed to a fresh series of challenges. Dropping school enrollments mean that schools in some of the most remote areas are closing, forcing more children to move or to travel long-distances to schools in “peri-urban” areas. As a consequence, many have been left behind by parents who have gone to work in cities, but they have also left behind their home villages, making it harder to maintain connections to family and friends and leading them to question their identities as members of farming communities. Li describes this as a new “double burden” for these rural children – separated from their parents and going to school in situations where they lack relationships with and trust in those around them.

The consolidation of schools also contributes to the number of students, some as young as 5 or 6, who have to board at their schools. That adds a whole new set of responsibilities for their teachers, some of whom have to spend 24 hours a day with their students – teaching them in the classroom and caring for them in the dorms. In response to this situation, in addition to the major focus on scaling up the Sunshine kindergartens, the Foundation also established the Companionship and Assistance Project to prepare young volunteers with training and supervision to act as school social workers who support the learning and mental health of the rural boarding school students, and help coordinate the relationships between students, parents, and teachers. These volunteers aim to help these children participate in schools, support their learning, and address issues of internet addiction and bullying.

Providing training and support for teachers

The lack of facilities and materials and the need to provide pedagogical and social and emotional support places a special burden on teachers in these rural areas. Many of the teachers are fresh out of college and have no experience with developmentally appropriate education or parenting. The declining population of primary school students means that the local education bureaus also asks some primary school teachers to serve in the kindergartens, but they don’t have experience with early childhood education either. Under these conditions, lecturing – telling students what to do – is common both for teaching in the classroom and for discipline in the dorms. Compounding the challenges for the early childhood educators, the declining population and decreasing enrollments leads to kindergartens with only 20 – 30 students, requiring consolidation into one mixed age class. With little training or experience with differentiation, kindergarten teachers generally end up trying to implement one curriculum for all their students, regardless of age or needs.

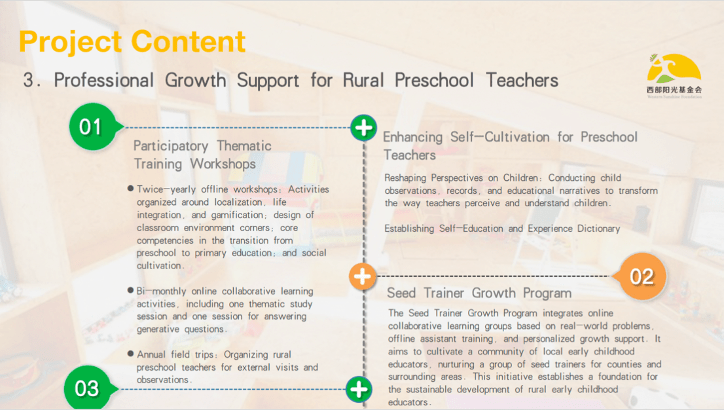

Given these challenges, the Foundation now provides early childhood teachers with materials and training to help prepare them for the unique demands of their rural context. For preschool teachers, for example, these efforts combine online teaching and research with offline training and study tours to provide sustained support.

Ongoing challenges

To carry out these initiatives, the Foundation constantly works to foster a wider understanding of the needs of rural children and the benefits of developmentally appropriate and student-centered education. That means confronting the pervasive belief that children’s only pathway to success is scoring high on exams – and leaving their rural homes for better schools and universities in urban areas. In turn, many donors, teachers and parents assume that success on exams depends on teacher-directed instruction further discouraging schools from trying to change their conventional practices.

This focus on exams makes things particularly difficult for the Foundation as many of their projects and activities aim to support students’ long-term growth and do not necessarily lead to quick or clear results in their academic performance. The difficulty in directly promoting success in school has gotten harder after COVID as many schools are less interested in sharing their space or cooperating with an NGO both because of safety concerns and because of the constant pressure to keep school time and activities focused on academic achievement. As a result, the Foundation has expanded programs and activities that engage students in activities after school or on weekends or during vacations, but many donors see these outside of school activities as having more limited impact.

To respond to these concerns, the Foundation has in some cases organized trips so that donors can visit the remote villages and engage in the same kinds of project design efforts as their young project volunteers. Li gave one example of a group of donors who spent several days identifying critical problems facing the local youth and trying to work with the students to address the problems. The donors chose to focus on school-related problems that involved developing activities within a school context, but then the school administration told the group of donors there was no time during the school day for the projects. Instead, the school told the donors they could only carry out the projects from 5 – 7 PM, when the students needed to rest. Through this kind of engagement, donors began to get a better sense of the constraints and possibilities for improvement. As Li said, donors may still be skeptical, but some develop a curiosity about the possibilities and are willing to see what happens.

More locally, the Foundation also tries to make the benefits of developmentally appropriate education visible by engaging local community members in their activities whenever they can. Those efforts include performances and exhibitions of the children’s work at community events and festivals and invitations for grandparents and other caretakers to join the students on hikes and other weekend activities.

Li also described one of her own experiences as a volunteer and how she built support for children’ activities in her village. In this case, the children she worked with, ranging in age from about 7 to 11, wanted to go see some of the other villages in their area. They had never made the trip beyond their local area because they had neither bikes nor the money to buy any. But they did have internet access. With her encouragement, the children turned to AI, asking “How can we get bikes when we have no money?” AI responded that new bikes can be created by recombining the parts of old bikes. Energized, the students searched the village for abandoned bikes and manage to build 12 bikes. “Of course,” Li explained, “the villagers opposed the whole project,” assuming that such young children couldn’t build the bikes and concerned that such a long trip and ride would be too dangerous. To change their minds and gain their support, after the bikes were built, Li and her colleagues organized a ride around the village to show the students’ accomplishments and invited the community to watch and participate.

Into the future

Looking ahead, the Foundation aims to continue to build the Sunshine kindergartens in underserved areas, and it is also developing a new model for community children’s centers that can support all kinds of activities after school, on the weekends and over the summer. All of this work, however, relies on those who can both recognize the challenges that rural children face and who can see the potential that they have. In terms of her own motivation, Li explained that she wants to continue to and expand this work both because of her love for the children she works with and because she herself was left behind in a small village. Despite considerable obstacles, she made her way to university, and she had the opportunity to learn how to communicate and to learn about child development and mental health. She wants to make sure that rural children today will not have to experience the same difficulties that she did and can learn how to take care of themselves at much earlier ages.